Guide to delirium care

Delirium care involves three main pillars: detection, treatment, and prevention. In this blog I provide a concise guide to the fundamentals of delirium care in adults outside of ICU settings. The same content is also provided at www.the4AT.com/deliriumguide.

More detail on delirium can be found in this article. This content is aimed at qualified health professionals and is provided for advice only.

DEFINITION AND BACKGROUND

WHAT IS DELIRIUM?

Delirium is a rapid change in mental functioning. It usually arises over hours or days. This fast speed of onset is characteristic of delirium and contrasts with dementia which typically develops slowly over months or years.

Most delirium lasts a few days, but in some cases (around 20%) it lasts longer and can take weeks or even months to resolve. In some patients there is only partial recovery and they do not return to their pre-delirium state. During a period of delirium the features can come and go (fluctuate). For example, a patient may be confused, disorientated and fearful overnight but appear more calm and less confused mid-morning.

People with delirium can present in different ways. The main abnormality is inattention, ranging from being barely responsive to voice (that is, severely reduced level of arousal), to being unable to engage in simple conversation and follow simple commands, to more subtle difficulties in maintaining focus over periods of 10-15 seconds.

People with delirium who are able to produce speech are usually confused, often showing an impaired understanding of what is happening to them. They are often distressed and anxious. They may also believe that they are at risk, for example feeling that they have been imprisoned or that staff or other patients are trying to harm them. Hallucinations are also common. They are mostly visual and can be very frightening.

Some people with delirium can appear very restless and hyperactive. This is often a consequence of fear in that they feel unsafe and want to leave to reach a place of safety or to be with family.

Delirium can be typed by psychomotor disturbance, with hyperactive, hypoactive (less responsive, drowsy) and mixed forms recognized. Hypoactive delirium is the most common but is more commonly undetected, particularly in older patients.

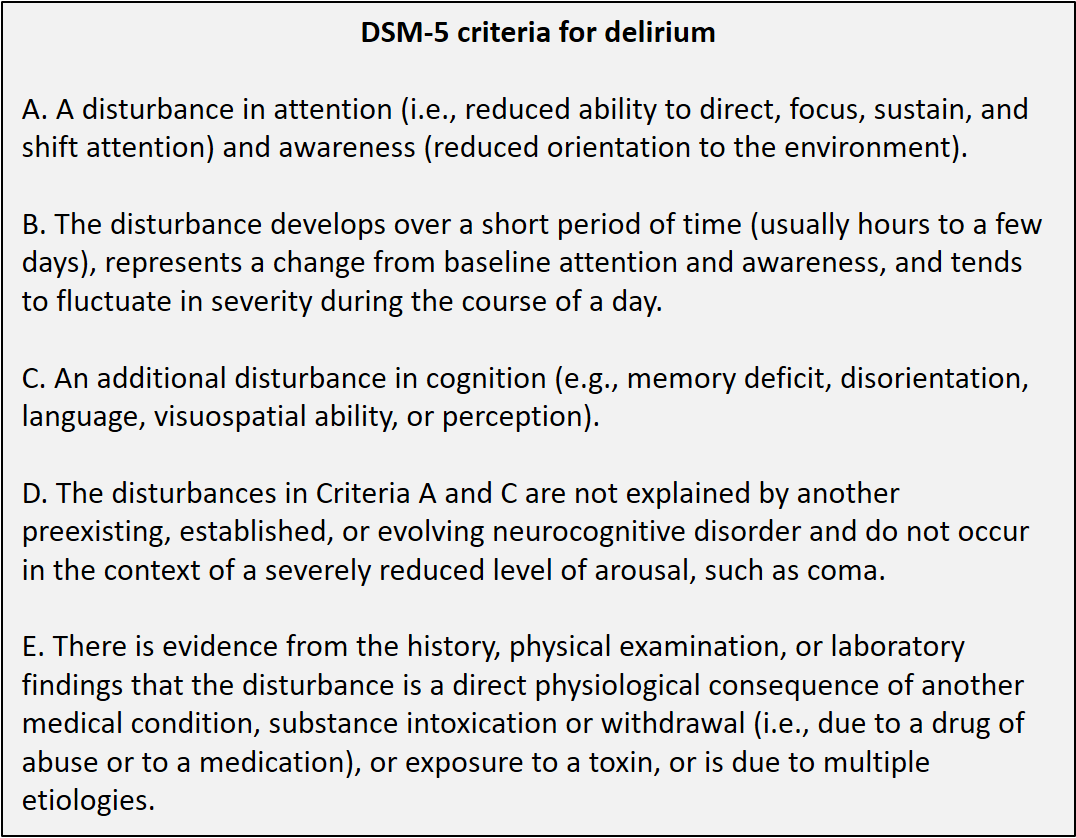

Below are the DSM-5 criteria for delirium. Note that the DSM-5 Guidance Notes state that “Low-arousal states (of acute onset) should be recognized as indicating severe inattention and cognitive change, and hence delirium.” This means that there is no separate classification of states such as ‘stupor’ or ‘obtundation’. Reduced level of arousal above the level of coma that is of rapid onset is usually delirium.

WHAT CAUSES DELIRIUM?

Delirium is caused by anything that can rapidly disrupt brain functioning. There is a long list of potential acute medical causes, including: infections (commonly urine or chest, but any almost infection can trigger delirium), trauma, surgery, constipation, drug side-effects (e.g. opioids or benzodiazepines), and sudden drug withdrawal (e.g. antidepressants).

Physiological and metabolic changes happening at the same time as acute illness such as low blood oxygen, high blood carbon dioxide, low glucose, high or low sodium, or high calcium can also directly cause delirium.

Acute psychological stress caused by hospital admission, pain, discomfort, disorientation, fear, isolation, and so on, can also trigger delirium, particularly in patients with dementia. Sleep disruption is also a cause.

The pathophysiology of delirium is incompletely understood. Because the brain is so complex and its function can be disrupted in many ways, it is likely that there are multiple possible mechanisms of delirium. These include direct causes like depriving the brain of fuel (oxygen, glucose) and toxic effects from drugs, and indirect causes such as peripheral inflammation triggering inflammatory and neurotransmitter changes in the brain. Currently there is no single mechanism thought to be consistently present in delirium, and so there is no simple drug treatment available. This fits with drug trials which have not shown drugs to be effective in delirium treatment (though see below for the limited circumstances in which drug treatment as part of delirium care can be considered).

WHO IS AT RISK OF DELIRIUM?

Increasing age, dementia, frailty, multiple co-morbidities, and sensory impairments all increase the risk of delirium.

HOW COMMON IS DELIRIUM?

Delirium is very common in acute hospitals. One recent meta-analysis found an overall occurrence of delirium of 23% in medical patients. Particular groups are at higher risk, with 30% of older patients undergoing emergency surgery and 40-60% of intensive care patients developing delirium.

Importantly, in hospitals two-thirds of delirium is present on admission, with the remainder arising during the inpatient stay.

DETECTION OF DELIRIUM

Delirium is best detected by the use of tools. There are two main types of tool used in clinical practice: episodic tools and monitoring tools.

EPISODIC TOOLS (4AT, CAM, CAM VARIANTS)

Episodic tools are used at the front door (e.g. ED, medical admissions), around the time of surgery (e.g. immediately post-operatively, and at other times when delirium is suspected.

Episodic tools provide a good balance of sensitivity and specificity. They always require some bedside assessment including cognitive testing, and include an item that notes if there is a change from the patient’s baseline. This kind of testing is needed to inform DSM-5 criteria. Episodic tools give information that is close to providing a formal diagnosis, though clinical judgement is always required.

The 4AT is an example of an episodic tool. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) is an episodic tool when preceded by bedside cognitive testing and interview (it is sometimes used without cognitive testing and interview as monitoring tool but is not validated for this purpose). The bCAM, UB-CAM and 3D-CAM, which like the 4AT have built-in cognitive assessments, are other episodic tools.

Episodic tools involve cognitive testing and interview and are too long and burdensome (for both patients and staff) to be performed effectively multiple times per day for several days. Daily use of an episodic tool for a small number of days in high-risk situations or when assessing recovery from delirium is reasonable. However, completion rates and/or detection performance are low when episodic tools are used repetitively for longer periods. Effective longer-term ongoing inpatient monitoring requires use of shorter monitoring tools.

MONITORING TOOLS (NEWS2, SQID, MRASS, DOSS, NUDESC, RADAR)

Monitoring tools are used in inpatients to detect new onset delirium arising after hospital admission. They are done daily or more in inpatients. Because they are done frequently, monitoring tools are generally observational only, or involve a few seconds of interaction only.

Validated examples includes the National Early Warning Score - 2 (NEWS2) used in UK hospitals, the Single Question in Delirium (SQiD: ‘Is this patient more drowsy or confused than usual?’), the Modified Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (mRASS), the Delirium Observation Screening Scale (DOSS), the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (NuDESC), and the Recognizing Delirium as Part of your Routine (RADAR).

If a monitoring tool gives a score suggestive of possible delirium, this should trigger assessment using an episodic tool such as the 4AT. This will then provide a clearer picture of the presence or absence of delirium.

OTHER TOOLS

The CAM-ICU and the ICDSC (Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist) are widely used in practice, though almost exclusively in ICU settings. They are not validated for use in general settings. There are many other delirium assessment tools, but apart from the above list most are used for research. Single-item bedside tests such as Months Backwards or asking the patient the current year have been evaluated and show variable sensitivity to delirium. They have some value as initial screening tests but lack the specificity required to function as standalone tests. They are not suitable for repetitive use for several days on end because of practice effects. Like with monitoring tests, single-question tests if positive should trigger a more definitive assessment with an episodic tool.

TREATMENT OF DELIRIUM

The treatment of delirium is complex and challenging. It involves both addressing all the triggers and in parallel also managing the patient’s distress. Promoting recovery, keeping the patient safe, communicating properly with the patient and their family, and deciding on appropriate follow-up are also central to delirium care.

The SIGN Guidelines on Delirium recommends 8 domains to consider when providing treatment to an person with delirium. This systematic approach can be termed Delirium 8 and the domains are shown here:

[1] INITIAL CHECK FOR ACUTE, LIFE-THREATENING CAUSES

Once delirium is suspected, it is necessary urgently to rule out acute, life-threatening physiological disturbance or drug toxicity. Consider for example low blood oxygen, high blood carbon dioxide, low blood pressure or low glucose, or recent administration of an opioid.

[2] IDENTIFY AND TREAT CAUSES / OPTIMISE CONDITIONS FOR BRAIN RECOVERY

Assuming that any immediate danger has been treated or ruled out, it is necessary to search for underlying causes (often multiple). Patients often have more than one cause, and so it is important to be systematic rather than stop at treating the first apparent cause. Consider potential pathology in each organ system, any metabolic abnormalities, drugs and drug withdrawal, psychological factors (e.g. stress resulting from hospital admission), and so on.

Also think of all the ways that conditions can be optimised to help the brain recover. This involves aiming to restore normal physiology as much as possible, providing fluids and food appropriately, avoiding constipation, avoiding a urinary catheter if possible, reviewing drugs (reducing or stopping drugs that might be contributing, but never suddenly withdrawing drugs where this not recommended), providing psychological support (reassurance, reorientation, avoiding isolation, involving family, etc.), facilitating healthy sleep through non-pharmacological means, and so on.

[3] DETECT AND TREAT DISTRESS

People with delirium are often distressed. There are many accounts of people who have had delirium who state that they were extremely frightened and that for some it was the worst experience of their lives. Also important are accounts that report that staff can make a large positive difference through how they interact with distressed patients.

When delirium is detected, part of the assessment should always be to look proactively for signs of distress. The first step is to observe the patient carefully. Do they look frightened or anxious? Are they frowning? Are they restless? If the patient is able to engage in conversation, ask direct questions about distress, e.g. ‘Are you feeling worried about anything?‘, ‘Do you need me to contact your family?‘), etc. Informant history from family or staff who know the patient well can also be useful.

If there is distress, then look carefully for common causes:

Pain, acute urinary retention and thirst are often missed (particularly in trauma patients) and are readily treatable. If the patient has delusions or is experiencing hallucinations, reassurance and clear explanation of where they are and what is happening to them can help. Start by introducing yourself and saying what your role is, then provide information such as: ‘You are in hospital now’, ‘It’s lunchtime’, and ask if they have any questions. As much as possible, involve the family in the care, with a focus on reorientation and reassurance. A family presence at the bedside can make a large difference, and if this is not possible even a phone call with a family member can make a person with delirium feel safer.

Drug treatment as part of delirium care: Despite multiple trials there is no evidence that drugs are effective in treatment of delirium as a whole. That is, there is no reason to prescribe a drug as a ‘treatment’ for delirium just because delirium has been diagnosed.

However, when a patient with delirium develops severe distress, particularly in association with psychosis (delusions and hallucinations), and non-pharmacological measures have been ineffective, then expert consensus supports a limited role for the use of drugs. Assuming no contraindications (check), antipsychotics are first line in most patients (though do consider the potential special circumstances of alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal). Small doses of risperidone (250mcg) or haloperidol (0.5mg) can be used. Monitor the QTc interval. Good practice is to administer 1 or 2 doses and assess response, usually stopping the drug at that time. Where patients are physically at risk to themselves or others or where more sedation is needed for safe medical treatment, higher and more frequent doses are sometimes needed. However, the principle of single or very short courses of drugs then reassessment still applies. Benzodiazepines again at low doses (e.g. 0.5mg lorazepam) are an alternative to antipsychotics.

Patients should not be given antipsychotics or benzodiazepines for several days or weeks in the context of delirium. If the drugs tried first are ineffective in controlling the symptoms alternative drugs as well as other strategies including other causes of distress such as pain or dehydration should be considered. Ongoing administration of antipsychotics for several days or weeks can lead to parkinsonism, falls, malnourishment, and worsened cognitive impairment.

Note that a small minority of patients in general settings (<10% in the experience of the author) need any specific psychotropic drug treatment as part of delirium care. It is not justifiable for it to be normal for all patients with delirium on a given ward or unit to be prescribed drugs as a response to a delirium diagnosis. The mainstay of delirium treatment is not drugs but general, systematic non-pharmacological as outlined in Delirium 8.

[4] PREVENT COMPLICATIONS

Delirium is a risky condition. It is linked with higher rates of immobility, dehydration, malnourishment, aspiration pneumonia, slow progress in rehabilitation, deconditioning, falls and pressure sores. When delirium is diagnosed, the patient should be considered at high risk of these complications and the care plan should aim to mitigate the risk.

[5] COMMUNICATE WITH PATIENTS AND CARERS

Communication with patients and families is often omitted or done poorly. In particular, patients and families may not be informed of the diagnosis and what it means. This can have the consequence that they never know the diagnosis and instead think that it is dementia or another mental disorder. Using the word ‘delirium’ in the explanation, and providing access to leaflets or web links giving reliable information is essential in alleviating the uncertainty and worry that unidentified delirium commonly causes.

[6] MONITOR FOR RECOVERY

Most delirium resolves in 3-5 days, but around 20% of delirium persists for longer than this. Persistent delirium (which can be defined as delirium lasting 5 days or more) is associated with particularly poor outcomes. It is important to monitor for recovery in the days following diagnosis so that persistent delirium can be identified.

Monitoring for recovery can be done by assessing for improvement in the specific features of delirium that the person has, for example drowsiness or delusions. Tools such as the 4AT can be used to structure the assessment and if the delirium is persistent ongoing recording of positive scores on a delirium assessment tool is helpful in documenting and highlighting that the delirium is persisting or that it has resolved.

[7] REHABILITATION DURING DELIRIUM

Part of the treatment of delirium involves continuing engagement and, as far as possible, maintenance of normal activities. Rather than being left alone for hours without interactions or mobilisation, people with delirium should be encouraged to engage in conversation and to mobilise as much as they are able and safe to do. Additionally, rehabilitation from injuries or other insults should proceed as much as possible even if the person still has delirium. This can require modification of usual approaches to physiotherapy and occupational therapy.

[8] CONSIDER DEMENTIA / CONSIDER FOLLOW-UP

Many older people with delirium also have undiagnosed dementia. Cognitive testing is a routine part of the dementia diagnostic process but is not useful during delirium because the delirium itself affects performance on the cognitive tests. Instead, the possibility of dementia can be determined to an extent by the use of informant history, including use of the Informant Questionnaire for Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) which has been validated for use in patients with active delirium. If these assessments raise the possibility of dementia then appropriate follow-up may be indicated. This might involve cognitive testing and a functional assessment in 2-3 months if the delirium has definitely resolved.

Another reason for follow-up is if the patient has persisting symptoms and discharged from hospital with delirium. To ensure optimal ongoing care the patient should be monitored for recovery and if recovery is slow additional assessment may be helpful. Finally, some patients with delirium experience frightening delusions and hallucinations, and some can develop post-traumatic stress symptoms. These symptoms can be disabling and can be present long-term. If the patient has experienced these kinds of symptoms this should be recorded, and follow-up through primary care or another appropriate means offered.

PREVENTION OF DELIRIUM

Most delirium is present on admission, but around 30% of delirium arises after hospital admission. Of this studies suggest that 30-40% can be prevented. Importantly preventive strategies not only reduce the risk of delirium, but may also reduce its duration and severity. Therefore guidelines recommend that preventive strategies for delirium should be implemented for higher risk patients (typically defined as older patients in hospital, and/or patients with frailty and multiple comorbidities).

Factors targeted in systems of care aimed at reducing the risk of delirium reflect the multiple possible causes of delirium. Such factors include orientation and engagement, medication review, provision of spectacles and hearing aids, promotion of healthy sleep, early mobilization, pain control, prevention, early identification and treatment of postoperative complications, adequate hydration and nutrition, avoidance of constipation, supplementary oxygen (if required), avoidance of unnecessary ward moves, and for high-risk patients, assistance from their relatives and carers to deliver care.

Pharmacological prevention strategies are ineffective, with no evidence to support prophylactic medication. Use of bispectral index devices to guide the depth of anaesthesia may reduce the postoperative delirium.

Study findings suggest that some post-admission delirium arises as a result of preventable factors arising during hospitalisation. Therefore the degree of delirium prevention depends partly on the extent of suboptimal care that can then be modified. For example, if it is normal practice to administer drugs for sleep (which increase the risk of delirium) then a process that reduces this practice will reduce delirium. Yet some hospitals may already limit the use of such drugs, especially as new prescriptions. Similarly, processes of nursing care that limit dehydration, malnourishment, and prolonged immobility limit the influence of these common causes of hospital-acquired delirium identified in earlier studies.

Achieving systematic coverage of all these factors is challenging. Studies have used a variety of models to achieve this, usually with dedicated staff and in some models using volunteers. The financial and administrative costs of each system vary but the evidence suggests that delirium prevention is cost-effective given the additional costs of delirium.

DELIRIUM PREVENTION AT THE PRACTITIONER LEVEL

Patients at high risk of delirium can be assessed systematically for the above risk factors and appropriate actions taken. These can include simple processes such as ensuring that the patient is provided with their hearing aids and spectacles, treating constipation early, monitoring fluid intake, treating pain carefully, and ordering a medication review by an appropriately qualified professional.

DELIRIUM PREVENTION AT THE SYSTEMS LEVEL

Some delirium can likely be prevented through routine processes such as targets for early mobilisation, avoiding ward moves, family involvement, and a delirium-friendly environment including the provision of orientation and clear information, and measures to improve sleep quality such as keeping the ward quiet at night. Ideally institutions should have a formal system of care which implements and audits known means of reducing delirium risk.

The phenotype issue might seem potentially problematic from a theoretical standpoint, but from an empirical and indeed robustly scientific standpoint, the multiple routes via specific indicators is proven to work. I think that using short cognitive tests alone, as in the UB-2, is really quite different from the 4AT, because although you get not-bad sensitivity for most tests, the specificity is usually not that good when you test populations with the whole spectrum of dementia severity (you can get artificially high specificities if the dementia group is mild-moderate – we have found this in our studies of the Delbox/DelApp involving >1500 patients). In fact you can’t get to a ‘possible delirium’ score on the 4AT on cognitive test results alone unless the patient is untestable on cognitive tests.